- Home

- Mary Monroe

God Don’t Like Ugly Page 4

God Don’t Like Ugly Read online

Page 4

The house was falling apart, too. One night while Mama was sleeping, some plaster fell off the ceiling and almost crippled her. Another time, she slid through a hole in the kitchen floor that had been hidden under a thin rug. She was lucky she didn’t break both legs. The landlord was too cheap to repair anything. Lucky for us, most of the people Mama worked for, especially the men, wanted her there days and some nights. We became live-in help. I slept in so many basements, I developed a phobia, and to this day, I won’t enter one unless I’m good and drunk. One employer let us occupy his garage, where Mama slept in a big old easy chair with me on her lap. Our toilet was a big rusty bucket with no handle. We used old newspaper and brown paper bags for toilet paper. We bathed at the Rescue Mission facilities every other day.

At one house, when the weather was warm, Mama’s boss let me sleep in a large doghouse with some puppies. When the weather changed, I was transferred to his basement. I don’t know where Mama slept. But one night I slipped into the main house and headed for the kitchen. While I was standing there with my head in the refrigerator, I heard Mama’s voice coming from a back room. She said, “Hurry up, Mr. Cursey. My jaws is gettin’ tired.”

I followed her voice, which led me to the man’s bedroom. Mama was on her knees with her head between Mr. Cursey’s legs. He was butt naked. “Shet up, woman. You know you need this job, and you and your monkey need a place to stay,” he told her. I didn’t know what I was seeing, so I never told Mama.

A few days later, Mama made me pack again. Scary Mary was out of jail and we were moving in with her. She was now running a cheap boardinghouse for cheap women, and Mama was going to cook and clean for her.

I was told that I would be sharing a bedroom with Scary Mary’s daughter, Mott. I was happy about that until I saw Mott. She was fifteen and severely retarded. Though she looked normal, she had the mind of a three-year-old. At four, I was baby-sitting a teenage idiot who called everybody Mama, including me and the many men who came to the house, most of them white.

My life was far from normal. I was so unhappy it showed. Mama promised me that when the time was right, she would find us a decent home of our own, and I’d be able to be just like other little kids. Mama’s promise was the only thing that kept me from going off the deep end.

I liked Scary Mary. She was nice and generous, but she bullied people, so like everybody else I was afraid of her. The way she looked was enough to frighten anybody. She was so tall she towered over most people. Her voice was deep and throaty, almost a growl. She was a grim woman, aged hard in every way. Her brutal face was round and heavily lined with wrinkles and a continent of black freckles sprinkled all over her honey-colored nose. She wore a matted red wig and a lot of makeup. She was real heavy-handed with her lipstick; some days she spread on so much some of it ended up on her teeth. The wig didn’t cover her Elvis-like sideburns, but she did dye them so that they matched the wig.

One day, marching like a soldier, she entered her cluttered kitchen, where Mama and I were sitting at the table eating greens and corn bread. “Gussie Mae, get up off your rump and come he’p us out. Lorene got the cramps, and everybody else tied up,” she barked.

Mama gave me a strange look. Scary Mary looked from Mama to me, then back to Mama. It seemed like they were talking without using words.

I had no idea what was going on until years later. Mama’s friend was running a whorehouse, and she often pressured Mama to work for her. “Annette, you go round up Mott and y’all go to the store to get me some chawin’ tobacco and a jar of Noxzema face cream. Take your time,” Scary Mary told me, caressing her chin.

“Can I get me some candy?” I asked with a pleading look.

“You can get you one jaw breaker. One,” Scary Mary croaked. She slapped a five-dollar bill into my palm. I stood there looking at the money in my sweaty hand. “One more thing, you can keep the change. Just take your time gettin’ back…”

I took my time getting back from the store, but it wasn’t enough time away for me to miss what Mama was up to. I was sitting in the living room, gnawing on candy bars with Mott, when Mama stumbled from upstairs with two fat white men. Both of them were hugging her. She looked at me, then looked away real quick.

“I thought you was at the store, girl.” She shooed the men toward a back room and rushed up to me. “There is things here you don’t need to see!”

“I didn’t see anything, Mama,” I told her. Even if I had seen “something,” I would not have known what I was seeing.

It wasn’t long before Scary Mary ended up in trouble with the police again. Something about her batting a man’s head with a frying pan over some money he owed her. “A slight misunderstandin’. Them kissy-poo po’lice ain’t goin’ to hold Scary Mary for too long,” Mama insisted with a shrug.

We packed again and left Scary Mary’s house the next day. A family from our church took Mott in, and Mama and I moved in with one of the nervous white men I’d seen at Scary Mary’s house. I dreaded the thought of another basement, but there I was once again, sleeping on a pallet between a furnace and a washing machine.

Mama was always tired at the end of her workdays, but she always had time for me. She would read the Bible to me or sit around with her friends and brag about me. “My girl, she so smart. She read books and can speak proper as any white girl. Oh, she goin’ to go real far. She goin’ to be a big success. Just like me.”

I was smart. Smart enough to know that I was not about to be somebody’s slavish maid like my mama. I didn’t have to be. I wasn’t going to work myself into premature old age or an early grave like Mama seemed to be doing. At least not cleaning up behind a bunch of lazy white folks.

One evening, when we were in the kitchen of the next house we lived in preparing dinner, Mama said tiredly, “I want you to stay like you are forever; smart and good. It’ll keep you on the right track, and you’ll always be happy.”

Her voice seemed so weak and sad, I wanted to cry. It hurt me deeply to see her suffer so much just so we could continue living in such an ugly world. But what choice did we have?

“Yes, Ma’am.” Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Mama staring at me with pity.

“I pray no man don’t make a fool out of you.” It saddened me further when she shook her head.

She started washing collard greens in the sink. I was standing next to her, picking bugs off the greens.

“When I get grown we won’t have to eat greens every day. I’m going to get a good job in an office making lots of money,” I chirped. We had some type of greens almost every day. Greens and some creature like a coon or a rabbit that some man from our church had caught.

“Office job? You? Go read your Bible,” Mama ordered. Her threatening look told me I had a whupping on the way. She moved from the sink to the counter, where she started to cut up a yam to lay on the pan around the coon she was going to bake.

I was still standing at the sink rolling my eyes at that dead coon that still had his head on in a roasting pan on the counter.

“You know how many little colored girls would love to be in your shoes?”

“No, Ma’am,” I muttered.

“I slave every day so we don’t have to go on welfare. I’m realistic. We colored. I know ain’t nothin’ else I can do but cook and clean and raise white women’s kids. I don’t like it. It ain’t somethin’ I dreamed about doin’ when I was a young’n. All I ever really wanted was my own restaurant, where I would be the head cook. The kind of dream you talkin’ about—you might as well be talkin’ about gettin’ elected president of the U.S.A. It ain’t goin’ to happen. Except in your dreams. You ain’t got the moxy Scary Mary got. She didn’t get where she at that easy.”

“They put her in the jail—again,” I gasped.

Mama mauled the side of my head with her fist.

“Fix your lips! Anyway, you got to be…a certain type to get one of them uptown office jobs. Folks runnin’ offices, they don’t set girls like you at no desk to answer

phones and greet folks. You…”

“I know I’m ugly, Mama,” I said seriously. “I hear people saying so all the time. And, I’m fat.” Somehow I managed a smile. “I see ugly people all the time, and they get good jobs. Like Miss Garra, that dog-face lady you worked for. You told me she work with the mayor now in his office.”

“She white.”

“Well, Reverend Snipes say beauty only skin-deep. Real beauty come from the inside.”

Mama chuckled and shook her head. Then she moved across the floor and snatched a bowl from the table and started mixing some corn bread on the counter. “Oh, child, that’s just somethin’ plain people say to make them feel better.” She sighed, waving the bowl at me. “There ain’t a handsome person alive would trade places with no ugly person.”

“You think I’m ugly, too, Mama? People say…God don’t like ugly.” I left the sink and slid into a chair at the table and folded my arms.

Mama stirred the corn-bread mix with a long-handled spoon so hard she started sweating. She glanced at me for a moment with an exasperated look on her face. “You beautiful inside and out to me. It’s ugly ways God don’t like. Worry ’bout bein’ good, not ugly.” She paused long enough to pour the corn-bread mix into a greased skillet and slid it into the oven. “If you goin’ to fantasize, fantasize about somethin’ practical. A husband with a good job, good friends, a nice home full of young’ns that mind you and know the Lord.” Mama’s voice got real low, and she kept her eyes on the floor while she talked. “I only got one fantasy,” she revealed. “And it’s as big a fantasy as yours about workin’ in a big fancy office. It’ll never come true. At least not for me…”

“What is it?” I left the table and went to stand in front of Mama next to the hot stove. She sighed, then went to the sink and started cutting up the greens.

She shrugged. “Oh…it ain’t nothin’. Just a pipe dream that ain’t got no chance of comin’ true. I don’t care about no minks and furs and mansions like all them white folks I work for got. Compared to the white folks, I want so little out of life and seem like it’s goin’ to take me my whole life to get it, if at all. Just a whiff of luxury. Luxury all the white folks I work for knowed all their born days. Me, I’d be happy livin’ just two or three days of the good life, praise the Lord.”

Mama left the room and returned moments later with her hands full of travel brochures. Very shyly and without looking in my eyes, she said, “Other than runnin’ my own restaurant, the only other thing in life I want is to see the Bahamas before I die.”

“The Bahamas?”

“All them white women I worked for in Florida went there all the time. And for days after they got home, that’s all they talked about. Remember?”

“I remember that time Mrs. Jacobs brought me some seashells back from the Bahamas,” I replied.

“It ain’t just the money. I know I could scrape up enough to go…if I let a few bills slide for a few months or…uh…be nice to Scary Mary and do her a few favors. It’s just that I can’t afford to take the time off from work. White folks is so fickle and helpless. I was to leave for a day or two, and I’m liable not to have no job to return to. I can’t take that chance.”

“But, Mama, you can always find maid work. And even the meanest white folks would probably let you take a few days off if you asked.” Mama went to work even when she was sick. Sunday was the only day she had off, and she sometimes worked up to twelve hours a day. “Just wait until I get a good job. You won’t have to work so much. You can spend as much time in the Bahamas as you want, stretched out on a beach with somebody fanning you for a change.” Mama smiled and hugged me so hard it hurt.

CHAPTER 5

After two years, I still didn’t like Ohio, but I liked Franklin Elementary School. There were a lot of other kids in my first grade class who had come from down South. Because of our Southern accents, almost every time one of us spoke, the Ohio kids made fun of us. My accent was not nearly as thick as some of the other kids because right after moving north, I had started imitating the way the Northern kids pronounced certain words.

I had a nice teacher, who encouraged me to learn as much as I could. “Education is the key to success,” Miss Nipp told me. Mama worked for her three days a week, so Miss Nipp was nicer to me than to the other kids. Sometimes she gave me a ride home in her shiny blue Buick.

We were living in a gloomy, three-bedroom house on Mahoning Street in a run-down part of Richland, the neighborhood where most of the people on welfare and the criminals lived, when Mr. Boatwright moved in. Right across from us was the city dump. Day and night you could smell fried food and marijuana fumes coming from the houses and foul odors from the dump.

One evening when Miss Nipp drove me home, she stopped at a hot dog stand and bought me a foot-long hot dog. “I hope you have a pleasant evening, Annette,” she said when the car stopped in front of our house. The people in our neighborhood were not used to seeing fancy cars driven by white women on our street. I frowned at the nosy faces staring out of the windows in the house next door.

“I will, Miss Nipp,” I said, smacking on the last piece of the hot dog. She was a small gray-haired woman so dainty, the smell of my neighborhood overwhelmed her. She patted my forehead and coughed. “It doesn’t smell bad around here all the time,” I lied, opening the car door.

“I’m sure it doesn’t, Annette. Now you be sure and tell your mother I said hello and that I appreciate her handling my dinner party last night.” Miss Nipp smiled. She had given Mama the day off, which meant Mama had some unexpected time to spend with me.

I hated coming home to an empty house and having to wait so late to eat dinner. Knowing that Mama was home and dinner was ready or close to it, I ran up on our porch with eager anticipation until I entered our living room and saw that strange old man unpacking his things.

I didn’t sleep much that first night with Mr. Boatwright in our house. When I woke up the next morning I thought I had dreamed him. But within seconds I knew he was real. Before I could get my clothes on, I heard his voice downstairs. “Sister Goode, what kind of greens you want me to cook today, collards, mustards, or turnips?” he asked. I cussed out loud to myself, so I didn’t even hear Mama’s response.

By the time I got downstairs to the kitchen, Mama had her coat on and was about to leave for work. “Annette, you come straight home from school to start gettin’ acquainted with Brother Boatwright.” She smiled, smoothing my hair down.

I glared at him. “Yes…Ma’am,” I mumbled, hardly moving my lips.

“And you better mind him,” Mama added.

“Oh, me and Annette gwine to get along real good in no time,” he said, hands on his hips, smile on his face. He had on a gray-flannel housecoat that touched the floor.

I didn’t even eat breakfast that morning. I just sat at the kitchen table staring from one wall to the other while he sat in the living room watching TV. I left to go to school without saying a word to him.

Miss Nipp knew something was wrong the minute I entered the classroom ten minutes ahead of all the other kids. “Annette, are you all right? You look rather down this morning. Is there a problem?”

I had to take a deep breath before I could speak. “This old man moved in with us yesterday, and I don’t like him,” I admitted.

“A Mr. Boatwright? Your mother mentioned him to me the other day. And why don’t you like him?” Miss Nipp asked. She put her hand on my shoulder and started rubbing it.

“Uh…I don’t know,” I admitted. “He’s old, and I think he’s going to be…bossy.”

Miss Nipp patted my head and laughed. “Don’t be too hasty with your judgments. Your mother is not a fool. She knows what’s best for you. Give Mr. Boatwright a chance,” she advised.

The first few days living with a man in the same house were rough on me. Miss Nipp came to meet him and liked him, but I resented his presence. Mama made me stop roaming around the house in just my panties, and I couldn’t turn on the TV in the mo

rning until he got up. When he shaved he left nappy gray hair on the bathroom sink and pee all over the toilet seat and floor that he took his time cleaning up. But by the time he got settled in, my feelings started changing. He had brought a smell with him that reminded me of Daddy. A musty, pleasant odor I had only smelled on certain men. Every time he entered the same room I was in, I thought about my daddy, and in some ways it was like I had my daddy back. Mr. Boatwright won me over when he started giving me candy and doing all the housecleaning I should have been doing.

He hugged me a lot and rubbed me in various places on my body, and it felt good. He had the same sadness in his eyes my daddy and I had. Once, after he had given me my Bible lesson, he leaned over and said, “Gimme some sugar!” I closed my eyes and smiled, expecting him to brush his lips across my cheek or forehead. My eyes flew open when I felt his dry lips on mine.

“Will you be my daddy, Mr. Boatwright?” I pleaded, licking my burning lips.

“Girl…I’m gwine to be more than a daddy,” he informed me, kissing me the same way again. He patted my behind, and I laid my head against his lumpy bosom.

Mr. Boatwright quickly made friends with Mama’s friends in the neighborhood, and he joined our church. Reverend Snipes sometimes let him sing a solo on Sunday. “And now Brother Boatwright is gwine to honor us with one of his favorite hymns,” Reverend Snipes announced proudly. Reverend Snipes was a little, reddish brown man around Mr. Boatwright’s age who reminded me of a sad dog. He had a long, narrow face with droopy eyes, a nose that turned up at the end, and shaggy gray hair that stood up around his head like Methuselah’s.

Over the Fence

Over the Fence Mama Ruby

Mama Ruby The Upper Room

The Upper Room Every Woman's Dream

Every Woman's Dream Deliver Me From Evil

Deliver Me From Evil God Ain't Blind

God Ain't Blind The Company We Keep

The Company We Keep God Don’t Like Ugly

God Don’t Like Ugly Borrow Trouble

Borrow Trouble God Ain't Through Yet

God Ain't Through Yet Family of Lies

Family of Lies In Sheep's Clothing

In Sheep's Clothing Beach House

Beach House The Devil You Know

The Devil You Know God Don't Make No Mistakes

God Don't Make No Mistakes One House Over

One House Over Never Trust a Stranger

Never Trust a Stranger Lost Daughters

Lost Daughters Red Light Wives

Red Light Wives She Had It Coming

She Had It Coming God Don't Play

God Don't Play Remembrance

Remembrance God Still Don’t Like Ugly

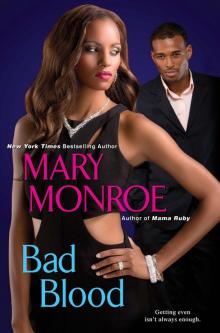

God Still Don’t Like Ugly Bad Blood

Bad Blood Can You Keep a Secret?

Can You Keep a Secret?